Using GitHub for Auto Deployments - Kubernetes Not Required

TL;DR

This post outlines a cost-effective and straightforward approach to deploying your web applications directly from GitHub to a Linux server, without needing Kubernetes. At its core, the process leverages GitHub infrastructure, Docker Compose, SSH, and a Linux server setup with an NGINX reverse proxy and LetsEncrypt for routing, TLS, and certificate management.

The process triggers automatic deployment upon a GitHub event such as a push to the main or master branch, or a new release. GitHub Actions automatically build and push Docker images to the GitHub Container Registry, then securely transfers the Docker Compose file to the remote server. The server pulls the new Docker image and starts the application using Docker Compose.

This system is not exclusive to any specific type of application; it is flexible enough to be adapted to any type of web application that can be containerized using Docker.

Important dependencies for this deployment process include:

DEPLOY_HOST: IP address or domain name of the deployment server.DEPLOY_USERNAME: SSH username for the deployment server.DEPLOY_KEY: Private SSH key for the deployment server.LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL: Registration email for Let's Encrypt certificate.

These secrets are stored in GitHub Action secrets for secure use throughout the end-to-end deployment process. The deployment strategy also needs Docker-enabled Linux server, NGINX for managing routing and a Docker Compose file.

Introduction

Every developer knows the struggle: you've written a fantastic application, it works flawlessly on your local machine, but now you need to get it out there in the world. The traditional cloud-native way often involves complex orchestration platforms like Kubernetes, which, while extremely powerful, can be overwhelming and overkill for smaller projects or applications with low traffic.

This is why we're going to explore an alternative and cost-effective approach in this blog post: deploying your web applications directly from GitHub to a Linux server, without the need for Kubernetes. This approach not only allows for affordable deployment of your applications but also promotes a quick and straightforward process, making it an excellent option for proof of concept or low-traffic applications.

This pattern we'll discuss consists of some core components: GitHub and its various functionalities, Docker Compose files, SSH for remote deployments, and a Linux server setup with an NGINX reverse proxy and LetsEncrypt companion containers for automation of routing, TLS, and certificate management.

By the end of this post, you will understand how to set up this deployment pattern. We will walk you through each step in detail, focusing on actionable, practical advice that you can apply right away.

Whether you're a .NET developer or working with other technologies, this pattern is flexible and can be adapted to your unique needs. As we progress, we will highlight how cost-effective and efficient this deployment strategy is for hosting your proof-of-concept, lower environment applications, or lower traffic systems, where horizontal scaling is not a necessity.

Understanding the Core Components

Before we get our hands dirty with deployment, let's take a moment to understand the essential components involved in this process. We'll also explain why we've chosen each one and how they contribute to our this cost-effective deployment pipeline.

GitHub and Its Functions

The backbone of our deployment pipeline is GitHub, a platform that provides a host of features to support our goals. Here are the key GitHub features we'll leverage:

- GitHub Actions: These are automated workflows that will handle the process of Continuous Integration (CI) for our application. It checks out code, sets up .NET Core, builds, tests, and creates releases. We'll go into detail about this in the practical section.

- GitHub Action Secrets: Sensitive information like login credentials, tokens, or keys shouldn't be exposed in your codebase. GitHub Action Secrets are encrypted and allow us to store such information securely, which is essential for building and pushing Docker images.

- GitHub Container Registry (GHCR): This is where our Docker images will be stored and versioned. GitHub Actions will build and push Docker images to GHCR, from where our Linux server will pull them during deployment.

- GitHub Repository: The central location where our application's codebase is stored. This is also where we'll configure GitHub Actions and store our Docker Compose files.

Docker Compose

Docker Compose is a tool that helps with the management of multi-container Docker applications. It allows us to define our application's environment in a YAML file (docker-compose.yml), enabling consistent setups across different environments. This will be installed on your target Linux server, where it will be used to pull Docker images and run our application.

Secure Shell (SSH)

SSH is a protocol used for securely connecting to a remote server. In our deployment process, we'll use SSH for copying Docker Compose files and executing commands on the Linux server, such as pulling Docker images and running Docker Compose.

This is done via GitHub Actions where we will use the ssh-action to securely transfer the Docker Compose file to the Linux server, and execute commands remotely.

Linux Server, NGINX, and LetsEncrypt

Our Linux server is where everything comes together. It's where our application will be hosted, and where the Docker Compose file will be executed. But that's not all; we'll set up NGINX reverse proxy on this server to manage HTTP requests and responses between clients and our application.

We're also adding LetsEncrypt into the mix. LetsEncrypt will work in conjunction with NGINX to automate routing, provide Transport Layer Security (TLS), and manage SSL certificates. This combination will ensure our application is secure and readily accessible.

By understanding these core components, we can now piece together our deployment pipeline. But before we proceed, it's essential to ensure you have access to the required tools. Make sure you have a GitHub account, Docker installed on your local machine, access to a Linux server, and the necessary knowledge to work with these tools. Don't worry if you're unsure about any steps; we'll guide you through each stage as we move forward.

Setting Up Your Linux Server

The heart of your web application deployment, the Linux server, requires proper setup and configuration to ensure the deployment and operation of your applications. Here, we'll be using Ubuntu 22.04 as our target server, although you can adapt these instructions for other distributions as well.

Firstly, you need to ensure you have a Linux server at your disposal. This could be a virtual private server (VPS) from any cloud provider, a dedicated server, or even a Linux machine in your local network (provided it can be accessed via GitHub Actions).

Once you have access to your server, follow these steps:

Installing Docker and Docker Compose

Docker is a crucial component that enables us to build, ship, and run applications inside containers. Docker Compose, on the other hand, streamlines the process of managing multi-container Docker applications. Here's how to install them:

- Update your server: Before we start, let's make sure our server has the latest updates. Run the following commands:

sudo apt update sudo apt upgrade -y - Install Docker: Docker provides an official guide to install Docker Engine on Ubuntu, which you can follow here.

By default, this should come with the latest version of Docker Compose. However, if you need to install Docker Compose separately, you can follow the official guide here.

After the installation, confirm that Docker and Docker Compose have been correctly installed by running docker --version and docker compose. The terminal should print the version of Docker and show command options for Docker Compose, respectively.

Setting up NGINX and LetsEncrypt

Next, we will set up NGINX and LetsEncrypt in Docker containers. These are responsible for handling client requests, routing, SSL encryption, and certificate management.

- Create the following YAML file on your Linux server:

version: "3.9"

services:

nginx-proxy:

image: nginxproxy/nginx-proxy

container_name: nginx-proxy

restart: always

ports:

- "80:80"

- "443:443"

volumes:

- conf:/etc/nginx/conf.d

- vhost:/etc/nginx/vhost.d

- html:/usr/share/nginx/html

- dhparam:/etc/nginx/dhparam

- certs:/etc/nginx/certs:ro

- /var/run/docker.sock:/tmp/docker.sock:ro

labels:

- "com.github.jrcs.letsencrypt_nginx_proxy_companion.nginx_proxy"

letsencrypt:

image: nginxproxy/acme-companion:2.2

container_name: nginx-proxy-le

restart: always

depends_on:

- "nginx-proxy"

environment:

- DEFAULT_EMAIL=you@example.com

volumes:

- certs:/etc/nginx/certs:rw

- acme:/etc/acme.sh

- vhost:/etc/nginx/vhost.d

- html:/usr/share/nginx/html

- /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock:ro

networks:

default:

name: nginx

volumes:

conf:

vhost:

html:

dhparam:

certs:

acme:

- Start the containers: Use the command

docker compose up -din the directory containing yourdocker-compose.ymlfile to start the NGINX reverse proxy and LetsEncrypt containers.

With Docker, Docker Compose, NGINX, and LetsEncrypt setup, your Linux server is ready for deployments. Note that these are one-off tasks. Once set up, you won't need to repeat them for deploying additional applications.

For subsequent deployments, GitHub Actions will take care of creating necessary directories and SCP copying the docker-compose.yml file from the repository to the target Linux server. This allows your deployment pipeline to be flexible, repeatable, and reliable.

GitHub: The Backbone of Your Deployment Pipeline

In this section, we'll explore how to set up a GitHub-based deployment pipeline, using GitHub Actions for automation, GitHub Secrets for security, and the GitHub Container Registry for Docker image storage. You'll see how these tools can provide a powerful, end-to-end solution for building and deploying your applications.

Understanding GitHub Actions

GitHub Actions allow you to create custom software development life cycle (SDLC) workflows directly in your GitHub repository. These workflows are described in YAML files and can be triggered by GitHub events (such as pushing code, creating releases, etc.), on a schedule, or manually.

In the provided YAML, the deployment workflow is triggered on three events:

- A new GitHub release is published.

- The build workflow has completed on

mainormasterbranches. - Manual trigger for rolling back to a specific release or redeploying the latest version.

The jobs are divided into two parts: push_to_registry and deploy_via_ssh. The first job builds a Docker image from the repository's code and pushes it to GitHub's container registry. The second job deploys the image to a remote server via SSH.

Configuring GitHub Action Secrets

GitHub Secrets are encrypted environment variables created in your repository settings. They're a secure way to store and use sensitive information in GitHub Actions, like credentials, SSH keys, tokens, etc. Without them, this sensitive information would be exposed in your public repository.

The YAML script uses the following secrets:

DEPLOY_HOST: The IP address or domain name of the server where the application is deployed.DEPLOY_USERNAME: The username used for SSHing into the deployment server.DEPLOY_KEY: The private SSH key for the deployment server.LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL: The email used for Let's Encrypt certificate registration.

These secrets can be set up in your repository settings under the Secrets section.

Go to `Settings` -> `Secrets` -> `New repository secret`

Leveraging GitHub Container Registry

The GitHub Container Registry is a place to store Docker images within GitHub, which can then be used in your GitHub Actions workflows or pulled directly to any server with Docker installed.

The following release.yml can be used with any dockerized application with a docker-compose.yml,docker-compose.prod.yml with an app and app-migration services, and the secrets above.

name: Release

permissions:

packages: write

contents: write

on:

# Triggered on new GitHub Release

release:

types: [published]

# Triggered on every successful Build action

workflow_run:

workflows: ["Build"]

branches: [main,master]

types:

- completed

# Manual trigger for rollback to specific release or redeploy latest

workflow_dispatch:

inputs:

version:

default: latest

description: Tag you want to release.

required: true

jobs:

push_to_registry:

runs-on: ubuntu-22.04

if: ${{ github.event.workflow_run.conclusion != 'failure' }}

steps:

# Checkout latest or specific tag

- name: checkout

if: ${{ github.event.inputs.version == '' || github.event.inputs.version == 'latest' }}

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: checkout tag

if: ${{ github.event.inputs.version != '' && github.event.inputs.version != 'latest' }}

uses: actions/checkout@v3

with:

ref: refs/tags/${{ github.event.inputs.version }}

# Assign environment variables used in subsequent steps

- name: Env variable assignment

run: echo "image_repository_name=$(echo ${{ github.repository }} | tr '[:upper:]' '[:lower:]')" >> $GITHUB_ENV

# TAG_NAME defaults to 'latest' if not a release or manual deployment

- name: Assign version

run: |

echo "TAG_NAME=latest" >> $GITHUB_ENV

if [ "${{ github.event.release.tag_name }}" != "" ]; then

echo "TAG_NAME=${{ github.event.release.tag_name }}" >> $GITHUB_ENV

fi;

if [ "${{ github.event.inputs.version }}" != "" ]; then

echo "TAG_NAME=${{ github.event.inputs.version }}" >> $GITHUB_ENV

fi;

- name: Login to GitHub Container Registry

uses: docker/login-action@v2

with:

registry: ghcr.io

username: ${{ github.actor }}

password: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

# Build and push new docker image, skip for manual redeploy other than 'latest'

- name: Build and push Docker images

uses: docker/build-push-action@v3

if: ${{ github.event.inputs.version == '' || github.event.inputs.version == 'latest' }}

with:

file: Dockerfile

context: .

push: true

tags: ghcr.io/${{ env.image_repository_name }}:${{ env.TAG_NAME }}

deploy_via_ssh:

needs: push_to_registry

runs-on: ubuntu-22.04

if: ${{ github.event.workflow_run.conclusion != 'failure' }}

steps:

# Checkout latest or specific tag

- name: checkout

if: ${{ github.event.inputs.version == '' || github.event.inputs.version == 'latest' }}

uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: checkout tag

if: ${{ github.event.inputs.version != '' && github.event.inputs.version != 'latest' }}

uses: actions/checkout@v3

with:

ref: refs/tags/${{ github.event.inputs.version }}

- name: repository name fix and env

run: |

echo "image_repository_name=$(echo ${{ github.repository }} | tr '[:upper:]' '[:lower:]')" >> $GITHUB_ENV

echo "domain=${{ secrets.DEPLOY_HOST }}" >> $GITHUB_ENV

echo "letsencrypt_email=${{ secrets.LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL }}" >> $GITHUB_ENV

echo "TAG_NAME=latest" >> $GITHUB_ENV

if [ "${{ github.event.release.tag_name }}" != "" ]; then

echo "TAG_NAME=${{ github.event.release.tag_name }}" >> $GITHUB_ENV

fi;

if [ "${{ github.event.inputs.version }}" != "" ]; then

echo "TAG_NAME=${{ github.event.inputs.version }}" >> $GITHUB_ENV

fi;

- name: Create .env file

run: |

echo "Generating .env file"

echo "# Autogenerated .env file" > .env

echo "HOST_DOMAIN=${{ secrets.DEPLOY_HOST }}" >> .env

echo "LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL=${{ secrets.LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL }}" >> .env

echo "IMAGE_REPO=${{ env.image_repository_name }}" >> .env

echo "RELEASE_VERSION=${{ env.TAG_NAME }}" >> .env

# Copy docker-compose and .env files to target server

- name: copy files to target server via scp

uses: appleboy/scp-action@v0.1.3

with:

host: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_HOST }}

username: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_USERNAME }}

port: 22

key: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_KEY }}

source: "./docker-compose.yml,./docker-compose.prod.yml,./.env"

target: "~/.deploy/${{ github.event.repository.name }}/"

- name: Run remote db migrations

uses: appleboy/ssh-action@v0.1.5

env:

APPTOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

USERNAME: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_USERNAME }}

with:

host: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_HOST }}

username: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_USERNAME }}

key: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_KEY }}

port: 22

envs: APPTOKEN,USERNAME

script: |

echo $APPTOKEN | docker login ghcr.io -u $USERNAME --password-stdin

cd ~/.deploy/${{ github.event.repository.name }}

docker compose -f ./docker-compose.yml -f ./docker-compose.prod.yml pull

docker compose -f ./docker-compose.yml -f ./docker-compose.prod.yml up app-migration

# Deploy Docker image with your application using `docker compose up app` remotely

- name: remote docker-compose up via ssh

uses: appleboy/ssh-action@v0.1.5

env:

APPTOKEN: ${{ secrets.GITHUB_TOKEN }}

USERNAME: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_USERNAME }}

with:

host: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_HOST }}

username: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_USERNAME }}

key: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_KEY }}

port: 22

envs: APPTOKEN,USERNAME

script: |

echo $APPTOKEN | docker login ghcr.io -u $USERNAME --password-stdin

cd ~/.deploy/${{ github.event.repository.name }}

docker compose -f ./docker-compose.yml -f ./docker-compose.prod.yml pull

docker compose -f ./docker-compose.yml -f ./docker-compose.prod.yml up app -d

In the provided YAML, the image is built and pushed to the registry in the push_to_registry job with the docker/build-push-action@v3 action.

- name: Build and push Docker images

uses: docker/build-push-action@v3

if: ${{ github.event.inputs.version == '' || github.event.inputs.version == 'latest' }}

with:

file: Dockerfile

context: .

push: true

tags: ghcr.io/${{ env.image_repository_name }}:${{ env.TAG_NAME }}

After building the Docker image, it is tagged and pushed to the GitHub Container Registry.

Using GitHub Action Secrets for Multiple Applications

In the YAML provided, the secrets are used in multiple places:

GITHUB_TOKEN: This is a system-generated token used by GitHub Actions to authorize interactions with the GitHub API and other services. Within the context of this workflow,GITHUB_TOKENis used to authenticate Docker, allowing it to push images to and pull images from the GitHub Container Registry. This is generated for you based on the permissions you give the GitHub Actions workflow.DEPLOY_HOST: This secret represents the hostname to which SSH connections will be made during the deployment phase. This could be an IP address or a subdomain, as long as it's correctly set with an A record pointing to your server.DEPLOY_USERNAME: This secret corresponds to the username required for logging into the deployment server via SSH. The value for this secret can vary depending on your server setup. For example, it could be 'ubuntu', 'ec2-user', 'root', etc., depending on the operating system and configuration of the deployment server.DEPLOY_KEY: This is the private SSH key used for remote access to your deployment server or application host. This secret is crucial for securing your SSH connections. It's important to generate this key securely and to store it safely within your GitHub secrets to ensure your server remains secure.LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL: This secret represents the email address used for Let's Encrypt certificate registration. Let's Encrypt provides free automated TLS (Transport Layer Security) certificates, which help secure the communication between your server and its clients. The email is used to receive important notices.

These secrets are utilized in both jobs, and they provide a secure way to use sensitive data across multiple steps.

# Copy only the docker-compose.yml to remote server home folder

- name: copy files to target server via scp

uses: appleboy/scp-action@v0.1.3

with:

host: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_HOST }}

username: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_USERNAME }}

port: 22

key: ${{ secrets.DEPLOY_KEY }}

source: "./docker-compose.yml,./docker-compose.prod.yml,./.env"

target: "~/.deploy/${{ github.event.repository.name }}/"

In the example above, secrets are used to provide the scp-action with necessary information to copy our docker-compose.yml,docker-compose.prod.yml, and generated .env file to the remote server.

How They All Work Together

Having a clear grasp of the components involved in our deployment pipeline, it's now time to delve into how they work together end to end to deploy your dockerized application. This section will help you visualize the bigger picture, breaking down the deployment process into a series of understandable steps.

Setting the Stage: The Deployment Process

The deployment process is a series of operations that involve our main actors: GitHub, Docker, and your Linux server. Here is how each step unfolds:

- The process begins when the user triggers an event such as a push to the

mainormasterbranch, creates a release, or manually triggers a dispatch. - The GitHub repository responds to this by initiating the workflow defined in our GitHub Action.

- The GitHub Action then retrieves the necessary secrets stored in GitHub Action Secrets. These are essential for secure operations such as logging into the GitHub Container Registry (GHCR).

- After logging in, the GitHub Action builds the Docker image from your application's source code and pushes the image to GHCR.

- Once the Docker image is securely stored in GHCR, the GitHub Action uses Secure Copy Protocol (SCP) to transfer the

docker-compose.yml,docker-compose.prod.yml, and.envfiles to your remote Linux server. - Using SSH, the GitHub Action then logs into the remote server and runs the database migrations service defined in your

docker-compose.ymlfile called theapp-migrateservice. - Finally, the GitHub Action instructs your server to pull the new Docker image from GHCR and start your application using Docker Compose.

Remember, this series of steps repeats each time a change triggers the GitHub Action, ensuring that your application is continuously integrated and deployed.

Flexibility

It's important to note that this process is not exclusive to a specific kind of application. The versatility of Docker allows us to adapt this process to deploy any web application that can be containerized using Docker, giving you a reliable and repeatable deployment process for a broad range of web applications.

Monitoring with LazyDocker

LazyDocker is a terminal UI for both Docker and Docker Compose. It allows you to monitor your Docker containers and services in real-time, giving you a visual representation of your application's health.

Part of what makes LazyDocker such an awesome tool is that you can use it anywhere from a terminal.

To run it as a docker container itself, you can use the following command.

docker run --name lazydocker --rm -it -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock -v ~/.lazydocker:/.config/jessedufffield/lazydocker lazyteam/lazydocker

Or better yet, use it as an alias in your .bashrc or .zshrc file.

alias lazydocker="docker run --name lazydocker --rm -it -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock -v ~/.lazydocker:/.config/jessedufffield/lazydocker lazyteam/lazydocker"

So you can run lazydocker easily from your terminal.

Concrete Example: Deploying a .NET Application

Let's see how you can use it to deploy a specific application. In this section, we will look at how to deploy a .NET application using the release.yml workflow.

It needs 3 files to run, as well as some GitHub Actions secrets like DEPLOY_HOST, DEPLOY_USERNAME, DEPLOY_KEY, and LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL.

docker-compose.yml

This file is used by Docker Compose to define the services that make up your application, so they can be run together in an isolated environment.

The release.yml expects a web application service called app and a database migration service called app-migration to be declared.

version: "3.9"

services:

app:

container_name: my_app

This file is the common denominator between your development and production environments. It is used by Docker Compose to build your application locally and by the release.yml workflow to deploy your application to your server.

We can control the behavior of Docker Compose for local development by using the docker-compose.override.yml file, which is not used by the release.yml workflow.

docker-compose.override.yml

The override file is used by default when calling the command docker compose up without any arguments.

version: "3.9"

services:

app:

build: .

ports:

- "5000:80"

Here we are telling Docker Compose to build the application from the Dockerfile in the current directory and expose port 80 on the container to port 5000 on the host machine. This allows us to access the application locally at http://localhost:5000.

docker-compose.prod.yml

This file is similar to docker-compose.yml, but it is specifically tailored for your production environment. Instead of building from the Dockerfile like in the development version, it pulls a specific image from a repository (ghcr.io/${IMAGE_REPO}:${RELEASE_VERSION}) which come from a .env file.

It also connects to an external network (nginx) which is our reverse proxy on our target Linux server.

version: "3.9"

services:

app:

image: ghcr.io/${IMAGE_REPO}:${RELEASE_VERSION}

restart: always

ports:

- "80"

container_name: ${APP_NAME}_app

environment:

VIRTUAL_HOST: ${HOST_DOMAIN}

LETSENCRYPT_HOST: ${HOST_DOMAIN}

LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL: ${LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL}

networks:

default:

external: true

name: nginx

Dockerfile

The Dockerfile is a text document that contains all the commands a user could call on the command line to assemble an image. In this example, it first creates a build environment based on dotnet/sdk:6.0-focal, copies your application code into the container, and restores any necessary .NET dependencies. It then switches to your application's directory and publishes your application in release mode. Finally, it creates the runtime environment based on dotnet/aspnet:6.0-focal, copies the built application from the previous stage, and sets the Docker entrypoint to run your application.

# Example dotnet app built from Dockerfile

FROM mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/sdk:6.0-focal AS build

WORKDIR /app

COPY . .

RUN dotnet restore

WORKDIR /app/MyApp

RUN dotnet publish -c release -o /out --no-restore

FROM mcr.microsoft.com/dotnet/aspnet:6.0-focal AS runtime

WORKDIR /app

COPY --from=build /out .

ENTRYPOINT ["dotnet", "MyApp.dll"]

.env (generated)

This file, .env, is a plain text file that stores environment variables for your Docker containers. Docker Compose automatically looks for this file in the same deployment directory as your docker-compose.yml and docker-compose.prod.yml files, and variables defined in .env can be read into the Compose file. The variables in this file could be secrets, URLs, or other configuration values. The .env file itself is typically not included in source control and instead, you might include a .env.example file to highlight the required environment variables.

This means when using docker-compose.yml locally, you can have a .env file with your local settings, and when using docker-compose.prod.yml on your server, you can have a .env file with your production settings, for example.

HOST_DOMAIN=razor-pages.web-templates.io

LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL=team@servicestack.com

APP_NAME=razor-pages

IMAGE_REPO=netcoretemplates/razor-pages

RELEASE_VERSION=latest

Applying the Deployment Pattern: A Practical Guide

The following step-by-step guide will show you how to create, prepare, and deploy your .NET application using best practices.

1. Building Blocks: Creating Your .NET Application

Kick-off your development process by creating your .NET application. In this example, we use the ServiceStack's x tool to create our web app from a template with the command x new web MyApp.

Your application will have a structure that may look something like this:

MyApp/

|-- MyApp/

| |-- wwwroot/

| |-- Configure.AppHost.cs

| |-- Program.cs

|-- MyApp.ServiceModel/

|-- MyApp.ServiceInterface/

|-- MyApp.Tests/

|-- MyApp.sln

|-- Dockerfile

|-- docker-compose.yml

|-- docker-compose.prod.yml

|-- .gitignore

2. Join the Hub: Pushing Your Application to GitHub

Once your application is set up, you can push it to GitHub. JetBrains Rider IDE has a handy "Share On GitHub" functionality that streamlines this process. Here's how you use it:

- Right-click on your solution.

- Select

Git -> GitHub -> Share Project on GitHub. - Enter your repository name and description.

- Click

Share.

Your .NET application is now on GitHub, ready for collaboration and continuous integration.

3. Implementing GitHub Actions for CI

To automate the build and test process every time you push to your GitHub repository, you can use GitHub Actions. A minimal .NET workflow file, build.yml, can be created and placed in the .github/workflows directory. Here's a minimal example:

name: Build

on: [push]

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Setup .NET

uses: actions/setup-dotnet@v1

with:

dotnet-version: '6.0.x'

- name: Restore dependencies

run: dotnet restore

- name: Build

run: dotnet build --no-restore

You can also add a test step to run your tests here.

This will run alongside any other workflows, like the release.yml outlined above, to ensure your application is always in a deployable state.

When the Build step completes, it will trigger the release.yml workflow.

4. Setting Up and Using GitHub Action Secrets

Next, you'll need to create secrets for sensitive data. In GitHub, you can store them as "Secrets". Follow these steps:

- Go to your GitHub repository and click on

Settings. - Click on

Actions->Secretsin the left sidebar. - Click on

New repository secret. - Enter the

NameandValueof the secret. - Click on

Add secret.

Create the following secrets:

DEPLOY_HOST: This secret represents the hostname to which SSH connections will be made during the deployment phase. This could be an IP address or a subdomain, as long as it's correctly set with an A record pointing to your server.DEPLOY_USERNAME: This secret corresponds to the username required for logging into the deployment server via SSH.DEPLOY_KEY: This is the private SSH key used for remote access to your deployment server or application host.LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL: This secret represents the email address used for Let's Encrypt certificate registration.

5. Finding Your Home: Create an A Record DNS Entry

To link your domain to your server, you need to create an A Record DNS entry. Here's a generalized step-by-step:

- Go to your DNS provider's website and sign in.

- Find the domain you want to update and go to its DNS records.

- Create a new record. For the type, select

A. - Enter your server's IP address in the

ValueorPoints tofield. - Save the changes.

Now, you can populate the DEPLOY_HOST secret in GitHub with your DNS.

This will be used by the release.yml workflow to deploy your application to your server via SSH.

6. Configuring Linux Server with Docker

By now, you should have a Linux server with Docker installed, and the NGINX reverse proxy with LetsEncrypt running, as we did in the previous section.

Your server will also need to be accessible via SSH on port 22 so that GitHub Actions can deploy your application.

7. Commit Change and Deploy Application

Now, commit any changes and push to your GitHub repository. If you've set up your GitHub Actions correctly, the CI will kick off. After a successful build, your application will be deployed and accessible from your specified domain.

Deploying Multiple Applications on the Same Server

Same Pattern, Multiple Applications

One of the core strengths of Docker is the ability to isolate and manage applications in their individual containers. This means you can deploy numerous applications, each from its separate GitHub repository, onto the same Linux server. All these applications can coexist and operate independently, provided each one is correctly dockerized. The release pattern remains unchanged and consistent to apply.

1. MyApp1/ -> GitHub Repo 1 -> Docker Image 1 -> Server (Container 1)

2. MyApp2/ -> GitHub Repo 2 -> Docker Image 2 -> Server (Container 2)

3. MyApp3/ -> GitHub Repo 3 -> Docker Image 3 -> Server (Container 3)

Organization Secrets

To maintain a streamlined deployment process when dealing with multiple applications, you can utilize the GitHub Actions' Organization Secrets. This feature allows secrets to be shared across multiple repositories in an organization, which saves time and reduces redundancy. The only secret that needs to be set up individually for each repository would be the DEPLOY_HOST and corresponding DNS for each application.

To set up organization secrets:

- Go to your GitHub organization's settings.

- Click on

Secretsin the left sidebar. - Click on

New organization secret. - Enter the

NameandValueof the secret. - Click on

Add secret.

Each deployed application now shares the organization-level secrets, streamline the setup process for new applications to a new DNS entry and DEPLOY_HOST environment variable.

And since every GitHub Repository in the organization is unique, there is no conflicting files deployed to the same server.

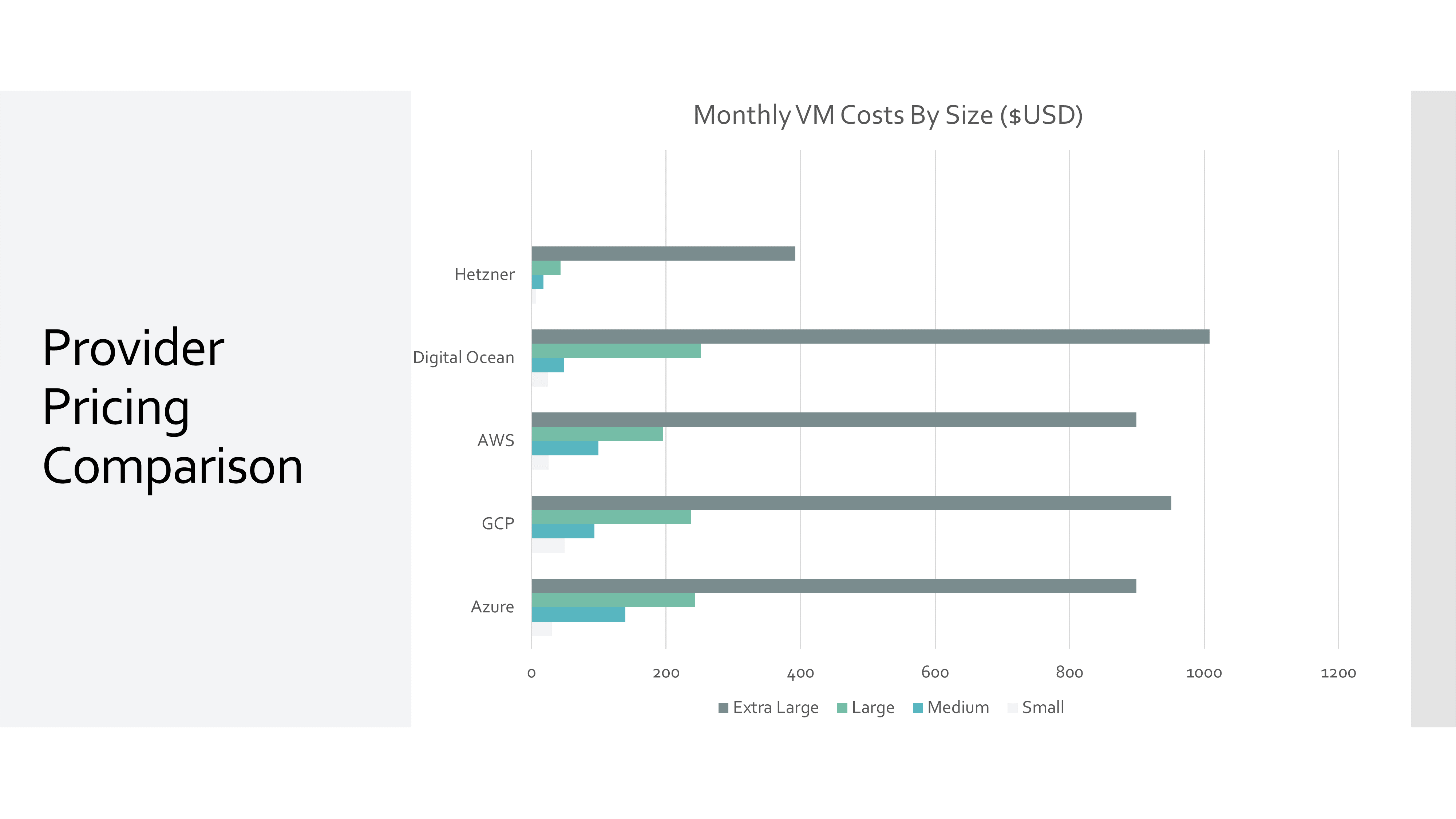

Cost Optimization: Using a Single Server

In our previous post,In pursuit of the best value US cloud provider, we looked for the most cost-effective cloud provider. We found that Hetzner Cloud offers the best value for money, with a powerful server costing around $10 USD per month. This means you can deploy multiple applications on a single server, saving you money and resources.

To host lots of our demo applications, we are doing exactly this, meaning we have a per container of less than $0.50 USD per month.

Conclusion

By avoiding Kubernetes, you can have less complex control your deployment process, and have more control over your applications. You can also save money by using a single server to host multiple applications. The release pattern is a flexible, yet effective way to deploy your applications, and it can be applied to any programming language or framework.

Feedback

If you have any feedback on this article, please let us know by commenting below, joining our Discord, GitHub Discussions, or Customer Forums.